For most people, the new economics of higher ed make going to college a risky bet.

In the fall of 2009, 70 percent of that year’s crop of high school graduates did in fact go straight to college. That was the highest percentage ever, and the collegegoing rate stayed near that elevated level for the next few years. The motivation of these students was largely financial. The 2008 recession devastated many of the industries that for decades provided good jobs for less-educated workers, and a college degree had become a particularly valuable commodity in the American labor market. The typical American with a bachelor’s degree (and no further credential) was earning about two-thirds more than the typical high school grad, a financial advantage about twice as large as the one a college degree produced a generation earlier. College seemed like a reliable runway to a life of comfort and affluence.

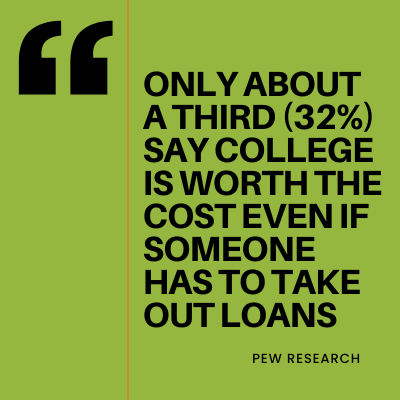

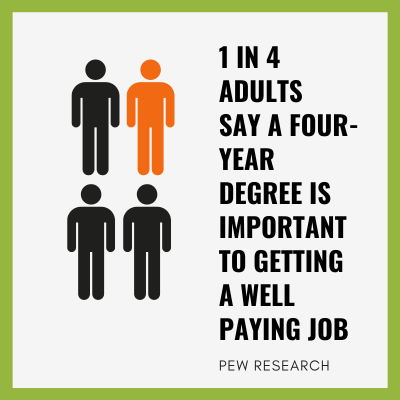

A decade later, Americans’ feelings about higher education have turned sharply negative. The percentage of young adults who said that a college degree is very important fell to 41 percent from 74 percent. Only about a third of Americans now say they have a lot of confidence in higher education. Among young Americans in Generation Z, 45 percent say that a high school diploma is all you need today to “ensure financial security.” And in contrast to the college-focused parents of a decade ago, now almost half of American parents say they’d prefer that their children not enroll in a four-year college.

The numbers on campus have shifted as well. In the fall of 2010, there were more than 18 million undergraduates enrolled in colleges and universities across the United States. That figure has been falling ever since, dipping below 15.5 million undergrads in 2021. As recently as 2016, 70 percent of high school graduates were still going straight to college; now the figure is 62 percent.

Outside the United States, meanwhile, higher education is more popular than ever. Our global allies and competitors have spent the last couple of decades racing to raise their national levels of educational attainment. In Britain, the number of current undergraduates has risen since 2016 by 12 percent. (Over the same period, the American figure fell by 8 percent.) In Canada, 67 percent of adults between 25 and 34 are graduates of a two- or four-year college, about 15 percentage points higher than the current American attainment rate.

Britain and Canada are not the outliers on this point; we are. On average, countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have increased their college-degree attainment rate among young adults by more than 20 percentage points since 2000, and 11 of those countries now have better-educated labor forces than we do, including not only economic powerhouses like Japan and South Korea and Britain but also smaller competitors like the Netherlands, Ireland and Switzerland. Americans have turned away from college at the same time that students in the rest of the world have been flocking to campus. Why? What changed in the last decade to make a college education — and higher education as an institution — so unappealing to so many Americans?

Read the full article here.